Adversarial Robustness Theory and Algorithms

CSCI-GA.2566 Foundations of Machine Learning Course Project

Overview

By looking through recent works in adversarial robustness

Keywords: Adversarial Robustness, Robust Optimization, TRADES, $H$-Consistency, Classification-Calibrated Surrogate Loss

Introduction

Deep neural networks have achieved remarkable success in recent years, yet their vulnerability to adversarial perturbations remains a significant concern. Goodfellow et al. (2015)

A key issue in addressing adversarial robustness is the fundamental trade-off between robustness and accuracy. This trade-off was formalized by Zhang et al. (2019)

At the same time, the concept of $H$-consistency has emerged as a critical property for surrogate loss functions, ensuring alignment between the surrogate loss and the true classification loss under adversarial settings. This concept guides the choice of training objectives, ensuring that improvements in surrogate loss directly translate into improved adversarial robustness.

The goal of this work is to revisit and connect key theories and results from foundational research on adversarial robustness. By analyzing these contributions, we aim to develop a deeper understanding of both the theoretical and practical aspects of adversarial defenses, ultimately bridging the gap between accuracy and robustness.

Methodology

Formulation of Robust Optimization

As shown in Ma (2018)

where $\mathcal{S} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^d$ represents the set of allowable perturbations. Minimizing $\rho(\theta)$ ensures that the loss remains small for all allowed adversarial perturbations. Thus, the search for robust models reduces to solving a well-defined optimization problem.

Standard optimization techniques, such as Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), cannot be directly applied to this saddle-point formulation because the adversarial loss involves solving the inner maximization problem at each iteration. The paper applies Danskin’s Theorem to address this issue. Specifically, for a differentiable function $g(\theta, \delta)$, where $\delta \in S$, the max-function $\phi(\theta)=\max_{\delta \in S} g(\theta, \delta)$ has a well-defined gradient, given by:

\[\phi^{\prime}(\theta, h)=\sup_{\delta \in \delta^*(\theta)} h^T \nabla_\theta g(\theta, \delta)\]If $\delta^*(\theta)$ is a singleton, then $\phi(\theta)$ is differentiable, and its gradient satisfies:

\[\nabla \phi(\theta) = \nabla_{\theta} g(\theta, \delta^*(\theta)).\]The paper establish the following Corollary, which states that the negative gradient $-\nabla_{\theta} L(\theta, x + \bar{\delta}, y)$ provides a valid descent direction for the outer optimization problem. Formally, let $\bar{\delta}$ be a maximizer of $\max_{\delta \in S} L(\theta, x + \delta, y)$. Then, as long as $\nabla_{\theta} L(\theta, x + \bar{\delta}, y)$ is nonzero, we have:

\[\phi'(\theta, h) = \sup_{\delta \in \delta^*(\theta)} h^T \nabla_{\theta} L(\theta, x + \delta, y) \geq h^T h = \| \nabla_{\theta} L(\theta, x + \bar{\delta}, y) \|_2^2 \geq 0.\]This result guarantees that $ -\nabla_{\theta} L(\theta, x + \bar{\delta}, y) $ is a descent direction for the max-function $ \phi(\theta) $, and also the saddle point problem defined earlier in this section.

In practice, the inner maximization is typically approximated using iterative methods such as Projected Gradient Descent (PGD), which ensures that $\delta^*$ remains within the allowable set $\mathcal{S}$.

We then utilize all the results above to give a principled approach to compute gradients for robust optimization efficiently.

Note that the ReLU activation function and max-pooling operations in neural networks may cause the objective function to be non-differentiable at certain points. However, these points are of measure zero and thus do not pose practical issues. Additionally, the inner maximization problem can be non-concave, but this can be addressed by selecting a concave subset of the domain and applying algorithms within that subset.

In summary, robust optimization reduces the challenge of adversarial robustness to solving a well-defined optimization problem. By explicitly considering worst-case perturbations and leveraging theoretical tools like Danskin’s theorem, we can design algorithms that effectively optimize for adversarial robustness.

However, a deeper issue arises from the saddle point optimization formulation itself:

\[\min_{\theta} \mathbb{E}_{(x, y) \sim \mathcal{D}} \left[ \max_{\delta \in S} \mathcal{L}(\theta, x + \delta, y) \right].\]This formulation focuses exclusively on minimizing the loss at adversarially perturbed inputs while neglecting the natural data distribution. The primary consequence is that the model is inherently forced to overfit adversarial examples, which introduces unnecessary complexity into the decision boundary.

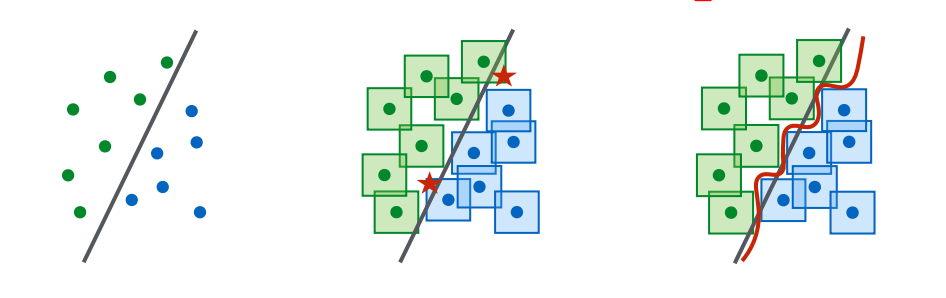

To illustrate this, consider the geometric impact of adversarial examples on the decision boundary. In the absence of adversarial perturbations, the model can rely on a relatively simple decision boundary, such as a linear separator, to classify natural data points. However, adversarial examples expand the input space that must be correctly classified, particularly in regions defined by the $\ell_\infty$-balls around natural data points. As a result, the decision boundary becomes significantly more complex and nonlinear to account for the adversarial perturbations, shown in Figure 1.

This phenomenon further increases the dependency on model capacity. To learn these complex decision boundaries, the model requires larger architectures, such as deeper layers or wider hidden units, which come with higher computational costs. Thus, the saddle point formulation inherently drives the model toward greater capacity, not necessarily because of a fundamental need for complexity, but due to the exclusive focus on adversarial data.

Establishment of Theoretical Framework and Improvement on the Adversarial Training

The key motivation of Zhang et al. (2019)

Write the natural generalization error as:

\[\mathcal{R}_{\text{nat}}(f) := \mathbb{E}_{(\boldsymbol{X}, Y) \sim \mathcal{D}} \mathbf{1}_{\{f(\boldsymbol{X}) Y \leq 0\}}\]Note that the two errors satisfy \(\mathcal{R}_{\mathrm{rob}}(f) \geq \mathcal{R}_{\mathrm{nat}}(f)\) for all $f$. The robust error is equal to the natural error when $\epsilon=0$.

Introduce the boundary error defined as:

\[\mathcal{R}_{\text{bdy}}(f) := \mathbb{E}_{(\boldsymbol{X}, Y) \sim \mathcal{D}} \mathbf{1}_{\{\boldsymbol{X} \in \mathbb{B}(\mathrm{DB}(f), \epsilon), f(\boldsymbol{X}) Y>0\}}\]It can be easily seen that

\[\mathcal{R}_{\text{rob}}(f)=\mathcal{R}_{\text{nat}}(f)+\mathcal{R}_{\text{bdy}}(f)\]as the first term \(\mathcal{R}_{\text{nat}}(f)\) includes all misclassified points regarding the accuracy, and the second term $\mathcal{R}_{\text{bdy}}(f)$ includes all the points that are classified correctly but within $\mathbb{B}(\mathrm{DB}(f), \epsilon)$, regarding the robustness.

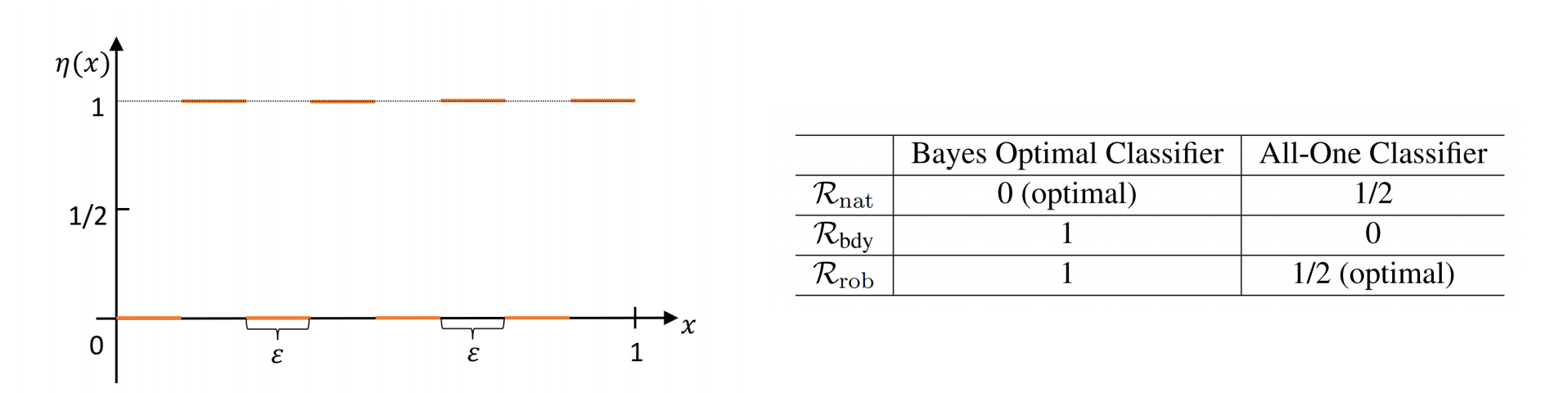

There is in fact a trade-off between \(\mathcal{R}_{\text{nat}}(f)\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{\text{bdy}}(f)\), showcased by the following toy example:

Consider the case $(X, Y) \sim \mathcal{D}$, where the marginal distribution over the sample space $\mathcal{X}$ is a uniform distribution over $[0,1]$, and for $k=0,1,\ldots,\left\lceil \frac{1}{2\epsilon} - 1 \right\rceil$,

\[\begin{aligned} \eta(x) & := \operatorname{Pr}(Y=1 \mid X=x) \\ & = \begin{cases}0, & x \in[2 k \epsilon,(2 k+1) \epsilon) \\ 1, & x \in[(2 k+1) \epsilon,(2 k+2) \epsilon)\end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

The results are shown in Figure 2.

Our goal is then to derive a good upper bound on $\mathcal{R}_{\text{rob}}(f)$ that we want to minimize, in the sense that a free hyper-parameter can be introduced to manipulate the trade-off between accuracy and robustness, and therefore a good algorithm can be derived to minimize this upper bound. We need several tools to achieve this goal.

Introduce the surrogate loss \(\mathcal{R}_\phi(f) := \mathbb{E}_{(\boldsymbol{X}, Y) \sim \mathcal{D}} \phi(f(\boldsymbol{X}) Y)\). Formally, for $\eta \in [0,1]$, define the conditional $\phi$-risk by

\[H(\eta) := \inf_{\alpha \in \mathbb{R}} C_\eta(\alpha) := \inf_{\alpha \in \mathbb{R}}(\eta \phi(\alpha)+(1-\eta) \phi(-\alpha)),\]and define $H^{-}(\eta) := \inf_{\alpha(2 \eta-1) \leq 0} C_\eta(\alpha)$.

The classification-calibrated condition requires that imposing the constraint that $\alpha$ has an inconsistent sign with the Bayes decision rule $\operatorname{sign}(2 \eta-1)$ leads to a strictly larger $\phi$-risk:

Assumption 1 (Classification-Calibrated Condition): Assume that the surrogate loss $\phi$ is classification-calibrated, meaning that for any $\eta \neq 1 / 2, H^{-}(\eta)>H(\eta)$, i.e., Bayesian estimator is always the minimizer.

One remark is that classfication-calibrated is a weak condition on the surrogate loss, by which ensures a rich class. Surrogate losses like Hinge loss, Sigmoid loss, Exponential loss, and Logistic loss are within this class.

Define the $\psi$ transform of classification-calibrated surrogate loss $\phi$ : $[0,1] \rightarrow[0, \infty)$ by

\[\psi=\widetilde{\psi}^{* *}\]where $\widetilde{\psi}(\theta) := H^{-}\left(\frac{1+\theta}{2}\right)-H\left(\frac{1+\theta}{2}\right)$. In fact, the function $\psi(\theta)$ is the largest convex lower bound on $\tilde{\psi}$. The value $H^{-}\left(\frac{1+\theta}{2}\right)-H\left(\frac{1+\theta}{2}\right)$ characterizes how close the surrogate loss $\phi$ is to the class of non-classification-calibrated losses.

Lemma 2.1

By using good properties of this $\psi$ transform, we can derive a tight upper bound in the sense of the following two theorems:

Theorem 3.1

Theorem 3.2

TRADES Algorithm

Heuristically, Zhang et al. (2019)

where $f(\boldsymbol{X})$ is the output vector of learning model (with soft-max operator in the top layer for the cross-entropy loss $\mathcal{L}(\cdot, \cdot)$, $\boldsymbol{Y}$) is the label-indicator vector, and $\lambda>0$ is the regularization parameter.

H-Consistency

Adversarial training methods, such as TRADES, rely on surrogate loss functions because they are differentiable and convex, therefore, easier to optimize. While surrogate loss functions are bounded, it is essential to ensure that minimizing the surrogate loss also leads to minimizing the true target loss. This connection is where the concept of $H$-consistency plays a pivotal role.

$H$-consistency is formally defined as:

where \(\mathcal{R}_{\text{target}}\) represents the true target loss, $\mathcal{R}_{\phi}$ is the surrogate loss, and $H$ is the hypothesis space. Intuitively, this inequality ensures that the gap between the true target loss and the surrogate loss is bounded by a function of their respective differences. In simpler terms, as the surrogate loss decreases, the true target loss cannot increase within a given set of models $H$. This property is critical for ensuring that adversarial training methods remain effective in practice.

However, TRADES’s surrogate loss has been shown to fail the $H$-consistency bound in certain scenarios

To address this limitation, a family surrogate loss function called Smooth Adversarial Losses was introduced in Awasthi et al. (2023)

Building on this improvement, the Principled Smooth Adversarial Loss (PSAL) algorithm was developed. PSAL outperforms TRADES and other state-of-the-art methods in terms of both clean accuracy and robustness to adversarial perturbations. This demonstrates that addressing the $H$-consistency limitation of TRADES can lead to more reliable adversarial training frameworks.

Future Work

In TRADES, a hyperparameter $\lambda$ was introduced to balance the trade-off between accuracy and robustness. However, $\lambda$ does not influence the theoretical proofs of the bounds and is only constrained by the loose condition $\lambda > 0$. Which is a reasonable and intuitive hyperparameter for empirical tuning. However this might also suggests that there is significant room for further research and development to improve the algorithm.